Introduction

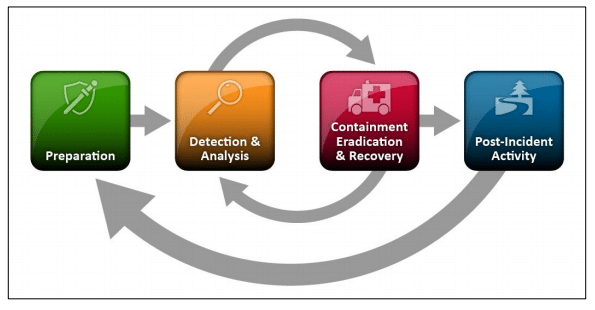

The NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) Incident Handling Process is a structured approach for managing security incidents, problems, and events. This process is detailed in NIST Special Publication 800-61, titled “Computer Security Incident Handling Guide”. The goal is to help organizations - particularly federal agencies, but also others in the private sector - manage incidents effectively by preparing for, detecting, analyzing, containing, eradicating, and recovering from incidents.

The NIST Incident Handling Process is divided into four main phases.

- Preparation - Implementing network defenses, policies, procedures, and the need for an incident response team with sufficient resources.

- Detection & Analysis - How to distinguish malicious activity from normal activity, and confirm the existence of a security incident so that appropriate individuals can begin to monitor and analyze the situation.

- Containment, Eradication, Recovery - Learning how to stop an incident from spreading, removing any malicious artifacts so that an attacker can no longer gain access to compromised systems, and working to fix any security flaws that were exploited or discovered as a result of the breach.

- Post-Incident Activity - Reflecting on the incident and learning from any strengths and weaknesses that were presented, so that a similar event doesn’t occur in the future, or the team is better equipped and trained to respond.

Preparation

Preparation is a crucial aspect of incident response. Without the right teams, resources, or documentation, the incident response process will not be optimal. Proper preparation can prevent attacks before they occur and consists of two main groups: incident preparedness and active incident prevention.

Activities for incident preparedness include:

- Contact information for all stakeholders;

- An operations room for centralized communication and coordination;

- Documentation;

- Baselines for system management;

- Equipment for infrared scenarios, such as digital forensic toolkits.

Activities for active incident prevention include:

- Updated risk assessments;

- Client and server security;

- A user awareness and training program.

Although there’s no perfect preparation phase for the incident response process, it’s the first line of defense against potentially catastrophic damage.

Incident Response Plan

Incident response plans are crucial to ensure the response process is clear and defined, allowing responders to act swiftly. These plans must be continuously updated, and training must be regularly maintained so all employees involved in incident response are capable.

IRPs are generally divided into the following six sections:

- Preparation

- Identification

- Containment

- Eradication

- Recovery

- Lessons Learned

Preparation

This initial phase emphasizes the importance of meticulous planning and continuous training. It involves:

- Developing and testing response plans for various incidents.

- Ensuring the availability of necessary resources like hardware, software, and training.

- Continual training and performance evaluation of team members, including their specific roles ranging from security analysis to PR and communications.

Identification

This phase concentrates on recognizing and assessing an incident. Key considerations include:

- Determining the incident’s specifics such as timing, discovery method, affected systems, operational impact, and overall scope.

- Assigning criticality and impact levels to prioritize response efforts, especially when dealing with multiple incidents.

Containment

Focuses on preventing further spread of the incident. This involves:

- Implementing immediate actions like disconnecting compromised devices or shutting down systems.

- Considering the implications of containment actions on evidence preservation.

- Ensuring backups are available to replace affected systems without disrupting business operations.

Eradication

Involves thoroughly analyzing the incident and eliminating threats. Steps include:

- Analyzing the incident using frameworks like MITRE ATT&CK and various analytical methods.

- Removing any harmful elements introduced during the incident.

- Strengthening defenses to prevent recurrence, utilizing collected indicators of compromise.

Recovery

Aims to restore normal business operations. This involves:

- Ensuring that systems are clean and fortified before reintroduction into the production environment.

- Providing clear guidelines for restoring systems and ensuring their integrity.

Lessons Learned

Post-incident, this phase involves:

- Holding a meeting with all stakeholders to review the incident, focusing on what went well and what can be improved.

- Using insights from the incident to strengthen systems and response strategies, potentially leading to policy, procedural, or resource adjustments.

Incident Response Teams

A dedicated incident response team is crucial to properly respond to confirmed incidents and reduce the impact they have on the business, working to ensure continuity and reduce costs following a successful attack. By bringing together people with all the necessary skills, this team of specialists can be activated when an incident occurs, minimizing the time damage can be caused.

Members of the incident response team

- Incident Manager

- Security Analysts

- Forensic Analysts

- Cyber Threat Intelligence Analysts

- Management/C-Suite (CISO, COO, CTO)

- Human Resources (HR)

- Public Relations

- Legal

Inventory & Risk Assessments

To protect systems, we need to know what resources our organization actually has, so maintaining an updated inventory of assets can help monitor production systems, test environments, and other devices under our protection.

While ideally, we’d protect all systems, sometimes protecting certain assets isn’t feasible, and this is where risk assessments come into play. Using them, we can identify systems that hold high value for the company and thus require more protection compared to others. This is an important part of incident response: if multiple incidents occur simultaneously, it should be clear which incident has priority and whether the response should be immediate or can be delayed.

Asset Inventory

An asset inventory is a centralized and updated list of all IT resources within an organization. This typically includes:

- Desktops/laptops

- Servers

- Printers

- Internet of Things (IoT) devices (such as heaters, TVs, alarms, vending machines, and anything connected to the network)

- Network devices (firewall, switches, routers, ecc.)

- Mobile devices

Risk Assessment

A risk assessment is conducted to identify the most critical systems for the company, thus the most valuable. These systems require enhanced protection and priority, especially in the event of two simultaneous incidents, as the definition of priorities must be clear so that time and resources are concentrated in the right place.

When risks are identified (such as a system connected to the Internet, a system lacking patches, or a system critical to the company), appropriate measures must be taken to defend it adequately, but only to the extent of the risk itself. It makes no sense to spend €100.000 on security controls for a server that is not used for anything and does not face the Internet. By assessing the risk, the right amount of resources can be allocated to protect the system. As explained at the beginning of the course, there are four approaches to risk:

- Risk Transfer (e.g., purchasing insurance)

- Accept the Risk (a decision made not to spend resources because the impact would be low and the cost too high)

- Mitigate the Risk (implement security and other controls to protect the asset and reduce the risk)

- Avoid the Risk (an asset with too high a risk can simply be taken offline so it cannot be exploited)

Security measures

Host Defenses

A list of instruments to ensure an optimal host defense tactic.

- Host Intrusione Prevention/Protection Sysem

- Antivirus software

- Centralized logging

- Endpoint Detection & Response (EDR)

- Local Firewall

- Windows GPOs

Network Defenses

A list of instruments to ensure an optimal network defense tactic.

- Network Intrusione Prevention/Protection System

- Firewall

- Next Generation Firewall (NGFW)

- Web Application Firewall (WAF)

- SIEM

- Network Access Control (NAC)

- Web Proxy

Email Defenses

- SPF, DKIM, DMARC

- Antispam filter

- Data Loss Prevention (DLP)

- Sandboxing

- Attachments restrictions

- Security awareness training

Preventing Incidents

In summary, activities to perform for preventing incidents:

- Risk Assessment

- Host Security

- Network Security

- Malware Prevention

- User Awareness and Training

Detection & Analysis

The detection and analysis phase of Incident Response involves two sub-phases: detection, where tools like IDPs and antivirus software alert teams to incidents, and analysis, which requires understanding the attack’s nature and spread. This phase is crucial for preparing incident responders, who must document findings, prioritize actions, and ensure proper communication, often outlined in a communication plan, with relevant internal and external parties. Once these steps are completed, responders move to the next phase of the Incident Response process.

Attack Vectors

Organizations should prepare for all incident types but focus on common attack vectors:

- External/Removable Media: Malicious code via devices like USBs

- Attrition: Brute force attacks like DDoS

- Web: Attacks from websites or web applications, e.g., Cross-Site Scripting

- Email: Phishing with malicious attachments

- Impersonation: Man in the middle, spoofing, rogue wireless access points, SQL injection

- Improper Usage: For instance, using file-sharing software for sensitive data

- Loss or Theft of Equipment

- Other

Signs of an Incident

Detecting and evaluating incidents is challenging due to:

- Various detection methods with differing levels of detail and reliability, including NID/PS, HID/PS, antivirus software, log analyzers, and manual detection.

- High volume of potential incident signs, e.g., millions of alerts per day from intrusion detection systems.

- Need for specialized technical knowledge and experience for data analysis.

Incident signs are categorized as precursors (future incident signs) and indicators (signs of a possible or ongoing incident). Precursors are rare, but when detected, allow organizations to alter security postures to prevent incidents. Indicators are common and include alerts from intrusion detection sensors, antivirus software, system administrators noticing unusual filenames, configuration changes, multiple failed login attempts, suspicious emails, and network traffic deviations.

Precursors:

- Web server log showing vulnerability scanner activities

- Announcement of a new exploit that could be affect your organization

- Threat actor that could be attack

Indicators:

- Alert from an IDS showing a buffer overflow attempt to a database server

- Antivirus software alert when a malware is detected

- Sysadmin detect a filename with unusual characters

- Host record a change on its log configuration

- Email administrator detect a high number of emails with suspicious attachment

- Network administrator detect an unusual deviation of network flow

Incident Analysis

Incident analysis is challenging due to false positives from IDSs and the fact that indicators might not always signify an incident. Incident Handlers analyze ambiguous, contradictory, and incomplete symptoms to determine what happened. Technical solutions exist but the best approach is a team of experienced and competent staff. The Incident Response Team should rapidly analyze and validate incidents, follow a predefined process, and document each step. Initial analysis should determine the incident’s scope, origin, and method (tools, attack methods, exploited vulnerabilities), providing information to prioritize actions like containment and in-depth effect analysis.

Reccomendations

- Network and System Profiling: Monitor normal activities to detect anomalies. Use file integrity software for checksums of critical files and monitor network bandwidth usage.

- Understanding Normal Behavior: Incident response teams should study networks, systems, and applications to recognize their standard behavior and detect abnormalities.

- Log Retention Policies: Implement policies specifying how long data should be kept. Old logs can be vital for identifying patterns of previous reconnaissance activities or similar attacks.

- Event Correlation: Correlate logs and events from different devices and applications to understand the incident’s dynamics. Each device or application, like firewalls or applications, logs different information that, when combined, provides a complete picture.

- Time Synchronization: Use an NTP server to keep the date and time of all hosts synchronized, aiding in the proper correlation of events.

- Knowledge Base Maintenance and Use: Maintain a comprehensive database containing explanations of the significance and validity of precursors and indicators, including IDPS alerts, operating system logs, and application error codes.

- Internet Search Engines: Utilize search engines like Google to find uncommon behaviors or anomalies, such as the inappropriate use of a TCP port.

- Packet Sniffers: Employ packet sniffers to copy or duplicate network traffic for detailed analysis.

- Data Filtering: When time is limited, categorize and filter indicators to focus on the most significant and relevant data.

- Seeking Assistance: Collaborate with other organizations, sharing IOCs and TTPs with other CSIRTs for enhanced incident response and knowledge sharing.

Incident Documentation

The IR team should immediately document all facts regarding a suspected incident, maintaining the incident’s status and other pertinent information, including current status, summary, related indicators and incidents, actions taken, chain of custody, impact assessment, contact information for involved parties, evidence list, handler comments, and next steps.

Incident Prioritization

Prioritization is critical and should be based on:

- Functional Impact: Impact on business functions

- Informational Impact: Impact on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information

- Recovery Capability: Incident size and affected resources determine recovery time and resources needed.

Incident Notification

After analysis and prioritization, notify key roles including CIO, heads of information security, local information security officers, internal/external IR teams, system owners, HR (for employee-related cases), public affairs (for publicity-generating cases), legal departments (for potential legal ramifications), and national CERT. Notification can be via traditional (email, website, phone) or unconventional methods (in-person or written).

Containment, Eradicationan and Recovery

The containment, eradication, and recovery phase of the Incident Response (IR) lifecycle has two crucial sub-phases ensuring successful recovery from an attack.

Containment: This sub-phase can vary widely in approach, depending on the type of attack, such as spear phishing or ransomware. NIST outlines key criteria for containment strategies including potential damage, evidence preservation, service availability, required time and resources, effectiveness, and solution duration. Detailed records of all evidence found during the attack are vital for future prevention tactics and knowledge sharing within the cybersecurity community.

Eradication and Recovery: This sub-phase involves returning systems to their pre-attack state. Actions may include rebuilding computers from known good backups, removing malware, or resetting compromised account credentials. It also involves eliminating vulnerabilities exploited in the attack and enhancing security measures like password changes, patch installations, and network security fortification.

Short-term Containment

Short-term containment is a quick fix or cure, aimed at preventing further damage by the affected resource or user. Methods vary depending on the actual incident and tools available. Examples include disabling compromised Active Directory accounts, using security tools to isolate an infected device, blocking remote IP addresses known for command and control on perimeter firewalls, and using Web Application Firewalls (WAF) to block traffic with common elements to the attack.

Long-term Containment

Long-term containment is an enterprise-level solution that goes beyond merely resolving an incident to address its root cause, preventing future similar incidents. This might involve changing internal network structures to prevent lateral movements, patching exploited vulnerabilities, implementing new security tools, and ensuring accounts have only necessary permissions (Principle of Least Privilege).

Containment Measures

Perimeter Containment: Involves blocking incoming and outgoing traffic, using IDS/IPS filters to identify and block harmful traffic, applying Web Application Firewall policies, and using null route DNS to prevent internal hosts from finding and connecting to certain domain names.

Network Containment: Includes VLAN isolation, router-based segment isolation, port blocking, IP or MAC address blocking, and Access Control Lists (ACL) to regulate network host activities.

Endpoint Containment: Actions like disconnecting infected systems from the network, shutting down infected systems, applying local firewall block rules, and Host Intrusion Prevention System (HIPS) actions like device isolation.

Removing Malicious Artifacts

Malicious artifacts, such as installed malware, running processes, scheduled tasks, registry entries, or files generated by a keylogger, must be thoroughly removed during incident response. Missing any artifacts could allow attackers to maintain some control over the system. This includes removing registry keys used for malicious file execution, scheduled tasks on Windows systems, or Cron jobs on Linux systems.

Post-Incident Activity (Lessons Learned)

The most crucial part of the post-incident phase is learning and improving existing systems. Incident response teams should constantly engage in learning and growing to prevent threats before they occur and respond to emerging threats. NIST recommends holding a “lessons learned” meeting to address specific questions about the incident, staff and management performance, needed information, measures taken, potential improvements for future incidents, information sharing enhancement, corrective actions, future indicators to monitor, and additional tools or resources needed. Implementing the answers to these questions and returning to the preparation phase to learn from the attack is essential for enhancing the organization’s defense.

Incident Response Metrics

Impact Metrics

- Service Level Agreement (SLA): Agreements determining operational expectations, responsiveness, and responsibility.

- Service Level Objective (SLO): Specific metrics within the SLA to measure, such as critical virtual machine uptime.

- Alert Assignment Rate: Measures how accurately alerts in SIEM are assigned to the correct security team member.

Time-based Metrics

- Mean Time to Detect (MTTD): Average time taken by the security team to notice a security incident.

- Mean Time to Response (MTTR): Time from detecting an element to the security team intervening to resolve it.

- Incidents Over Time: Average number of incidents over a period to determine if there’s an increase or decrease in incidents.

- Repair Time: Time taken by incident responders and stakeholders to remedy the situation.

Incident Type Metrics

- Cumulative Number of Incidents by Type: Classifying incidents by type to provide an overview of areas needing improvement.

- Alerts Created per Incident: Analyzing the number of alerts created for a specific incident to understand defense improvement points.

- Cost per Incident (CPI): Analyzing the perceived cost of the incident to the affected company in various ways.

Reporting Format

There’s no standard format for incident reporting, but common sections in a report include:

- Executive Summary

- Incident Chronology

- Incident Investigation

- Appendix

Executive Summary

Provides a general overview of the incident in non-technical terms to clearly indicate the business impact. It should be easily readable and contain information important for executives, focusing on business risks, financial costs, and damages.

Incident Chronology

Provides the date, time, and brief descriptions of all key events during the incident, ensuring that the timeline is orderly and easy to read.

Incident Investigation

The main part of the report, documenting detailed actions and results of responders. All stages of the incident response lifecycle except preparation should be reported here, including Detection and Analysis, Containment, Eradication, and Recovery, and Post-Incident Activity.

Report Appendix

Used as a repository for the report, typically including images or figures referenced in the main body. This section might include extensive lists or tables that would occupy too much space in the main report body.